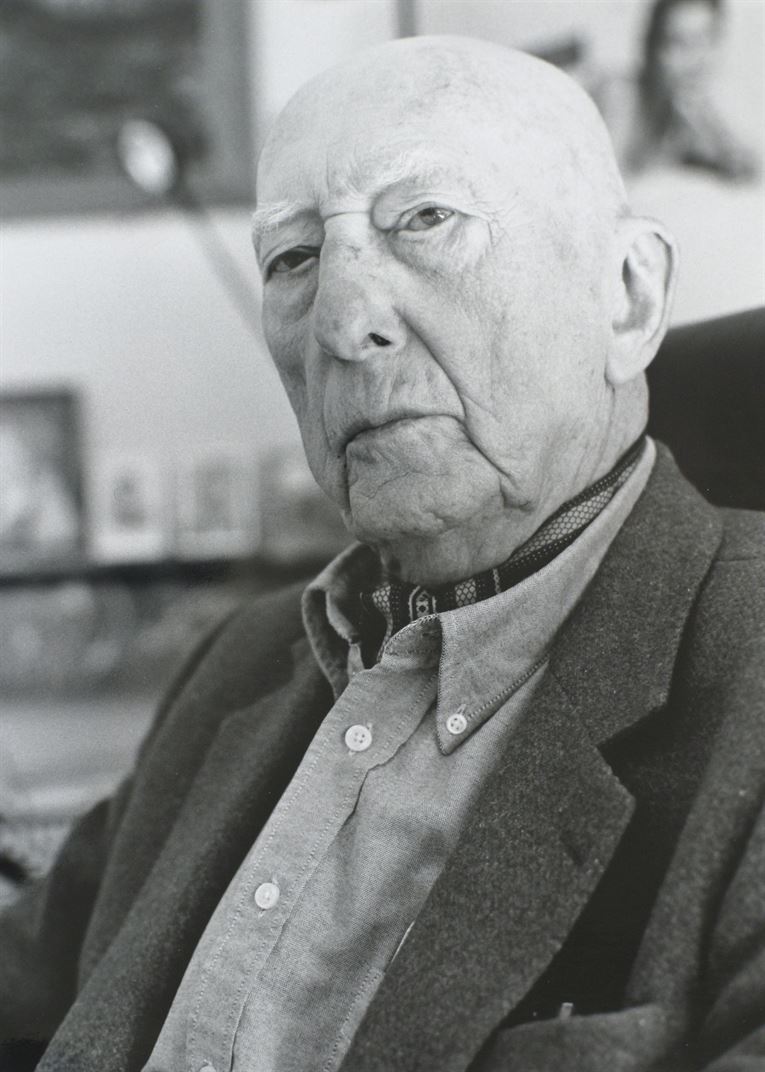

Arthur Haulot, was 28 when he was arrested by the Gestapo in Brussels in December 1941.

A socialist activist and early Resistance member, in July 42 he was part of a group of forty hostages sent to Mauthausen, then transferred to Dachau in November of the same year.

There he became a nurse. It was a strategic role: he helped the sick, of course - even though the treatment options were often derisory - but more generally, the infirmary was a place where you could hide someone, where you could discreetly exchange information, where you could prepare plans to sabotage the Nazi machine, however little, whenever possible.

He quickly became a representative of the Belgians, and as such was one of the founders of the International Prisoners' Committee, the origin of our CID.

Set up at the beginning of April 1945, the Committee was officially created on 29 April, headed by a Belgian resistance fighter, Albert Guérisse, who throughout his captivity, and until after the Liberation, would pass himself off as a Canadian soldier called Patrick O'Leary.

While waiting for the Liberation, which they knew was imminent, the men of the Committee tried to guess their guards' intentions : to execute the prisoners ? Evacuate them to another camp ? Or simply run away and leave them there ? And they devised strategies to thwart or minimize the effect of these different options, to save as many of their comrades as possible. He wrote in his camp diary on 6 April:

‘Personally, I feel responsible. Responsible for those who are still my camp mates today, who have the right to hope for a return home. It may depend on the decision of a few of us (he's talking here about the Committee), on our composure, on our will, to make this hope a reality. And tomorrow, back home, we will be responsible for the widows and children of our lost friends, responsible for the direction life will take’. (1)

So in the meantime, you hide your friends, delay the departure of convoys as much as possible, and watch for clues as to the attitude of the SS. Then came the evening of 28 April.

‘At 11pm, one of our most reliable agents said that the last groups of soldiers had left, and that the entire staff would follow. (…) We issue two instructions: to fill all possible containers with water; not to panic in the event of an explosion, and to maintain absolute, fierce discipline, whatever the events of the night or the following day might be. (…) At around 11.30pm, fifteen men were gathered in Block 24, clandestinely. (…) Now it was time to finish the job. It was no longer a question of preventing a departure that could no longer take place, of sabotaging orders that would no longer come. Later, at dawn, if the SS have indeed left, life in the camp must continue intact, order must be maintained, until the Allies bring Freedom. (2)

How could one tell the story of what happened next? In the morning, we noticed that the SS had left the camp. In their place, two combat groups stood guard. (…) The Committee was officially in session. In the afternoon, fighting broke out. (…) One watchtower after another raised the white flag. From the Committee set up in the Bücherei, we follow, breathless, the final stages. The soldiers from the last watchtower surrender. And a few moments later, a car appears: the Americans! Immediately, we were outside, Patrick and I in the lead. Two soldiers pass through the gate. One falls into my arms. I embrace him, he embraces me... and I realize it's a woman! An American war correspondent, the first American to enter a liberated Dachau. From then on, it was madness. The whole camp rushed against the gates. The SS prisoners, gathered on the other side, were booed. If they fell into our hands, they would be torn apart. The crowd roars with joy. It was impossible to calm them down. It took several hours, and the evening falls, to get the entrance cleared. (1)

Because it's not just hatred or joy that the crowd is shouting. It was also out of gratitude. Gratitude to the handful of American soldiers who now surrounded the little ‘jeep’ of their general: General Linden, who stood gazing at the mass of men who had gone mad with joy and whom he had just saved. (2)

That same evening, the Committee moved into the Jourhaus. And life goes on.

30th April. Paul offers to repatriate me. The General agrees. But I can't accept. In my thoughts, I see Camille again, and all the others, known and unknown, who have fallen around me over these three years. I can't leave. I have to save those who are still here, lead them back to their country, to their family. Lou, forgive me! But I wouldn't be a man, the man you want me to be, if I did otherwise. Beloved, you are there in my heart again today, burning and sweet. But I can't leave.’ (1)

That's the beauty, the strength of the Prisoners' Committee: this willingness of each of them to serve, the dedication of fifteen or so for the 32,000: after months or years of detention in hell, rather than returning to their families as quickly as possible, they chose to continue managing the daily life of the camp for several more weeks, caring for the deportees, particularly through a terrible typhus epidemic, and gradually evacuating them.

After Pat O'Leary's departure on 8 May, my father took over the chairmanship of the Committee for a month before leaving the camp in his turn on 6 June. Half-serious, half-joking, I sometimes heard him introduce himself as ‘the last commander of the Dachau camp’, obviously provoking surprise and incomprehension in the eyes of his interlocutors.

On 9 June 1945, he arrived in Brussels. Of his group of 40 deported in 1942, only 4 returned.

He soon returned to Germany, where he travelled until February 1946 as a witness at the Dachau trial and as a journalist.

Then began a new life for him. Through a brilliant international career in tourism, the publication of numerous books, the organisation of international congresses of poets and an unstinting commitment to the work of remembrance, in particular within the framework of the CID, of which he remained vice-president until the end, the rest of his life was devoted to bringing the most different, even opposing, men and women to get to know each other, to meet and to talk to each other.

He had no regrets about his experience in the concentration camp: ‘If I get out of here alive,’ he used to say, ‘I'll never regret going in’, so keenly did he observe the behavior of the other inmates and his own: he himself knew that he would never sink any lower than he had in Dachau, and would never rise any higher either.

On 8 May 2005, at the age of 91, he testified for the last time before the Belgian Senate during the Victory anniversary celebrations. Tired but happy, he returned home, his head full of projects. He suffered a stroke later that night. He died on 24 May 2005, happy with a full life.

(1) : J’aI voulu vivre, éd. Vie Ouvrière, 1987

(2) : Mauthausen-Dachau, éd. Le Cri / Vander, 1985