In November 1944, I was taken to Dachau with a group of political prisoners from Hungary by an SS unit stationed in the fortress of Komarom. Here, the Hungarian authorities delivered us and left us to the mercy of their allies. Instead of the fixed daily routine of the Hungarian prisons, we did not know what awaited us here in the future.

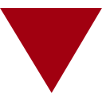

But, let us start form the beginning. Technical High School in Novi Sad, October 2, 1941, second graders’ classroom: the janitor whispers something to the teacher, who calls out – „Pavle Katić to the headmaster“. Two police agents of the occupying authorities were already expecting me there and took me to the centre for investigations of anti-state activities. The usual atrocities, beatings to exhaustion, in their effort to expose an illegal network of the Resistant Movement members. In this way, several thousand patriots, activists, participants in the People’s Liberation Movement in Novi Sad were arrested between 1941 and the town’s liberation in 1944. Many of them lost thier lives in the process, others were sentenced to death, and the majority served time sentences in Hungarian prisons.

For my illegal/resistance activities I was sentenced to 5 years imprisonment. I spent a part of that period in a military prison in Budapest, followed by a certain period in the largest Hungarian prison at Vac, where one building alone housed about one thousand political prisoners from the occupied region of Bačka, in Vojvodina, the northern part of Serbia. I suffered the longest period of incarceration in the prison at Satoraljaujhely, a small town in the north-eastern tip of Hungary. I endeavoured to compensate for the interrupted school education by reading, studying and, above all, by ideological and political discussions in which I took part. On March 22 of 1944, an escape revolt and liberation fight was attempted, but was thwarted in a bloody reprisal.

As the Fascist forces retreated under the onslaught of the Soviet army, political prisoners were taken to the western part of the country, such as the Komarom fortress, mentioned in the beginning of this story. When we ended up at the Dachau concentration camp, we quickly settled into the regime and fixed rules. The kapo, usually a criminal prisoner, assigned by the camp administration, was the supreme ruler of the barrack – he brought to order the unmanageable prisoners with a stick or a bludgeon. Each of the four rooms of a barrack housed about 200 camp inmates, on three-level wooden bunk „beds“. It meant that three to four people lay in one bed („box“) littered with some straw, usually in two’s, heads to toes.

A special feature of every camp was the so called „headcount“, the establishment of the number of persons in the barrack. It involved a line-up out of doors (Appelplatz) or in a tight space between two barracks. The headcount would first be done by the kapo, and afterwards by a German officer from the camp administration. This procedure often lasted for hours, as punishment, or in case the numbers did not match. I still remember acutely how hard it was to stand in the open, at below minus 10 degrees, dressed in inmates’ cloth shirts or gowns only.

A few days upon our arrival, an officer of the camp administration did a screening and allocation of newly arrived prisoners to work posts. German factories were, due to frequent air raids, almost in ruins, but were somehow still in operation, thanks to the newly brought prisoners. That same day, the selected labor group was transferred to a labour camp near Augsburg. In improvised sleeping quarters, a former aircraft hangar, the inmates were gathered, and in an empty space several German soldiers were pushing forward three prisoners with their hands tied behind them. The officer read a short sentence – for an attempted escape, sentenced to death by hanging... The execution was brief, nooses round their necks and the chairs kicked from underneath them.

Troublesome waking and off to work at the break of dawn was coupled by a shocking discovery that under the straw pillow where I had put my leather boots before going to sleep – there was nothing. No trace of my only personal item that remained to me since I came to the camp. Instead, I got brutally reprimanded and hit by the kapo, who hurled a pair of wooden clogs to me and pushed me into the line moving towards an improvised railway station. A short ride and we were at a half-demolished workshop walled with tinplates. We were constantly followed by SS uniforms accompanied by dogs, and in the workshop we were allocated individually to help the German workers. After a short explanation a hammer was shoved into our hands, and we were to bend the aluminium sheet onto the template held by the bench-clamp. I found out – this was part of the Messerschmitt plane factory, which still produced spare parts. In the morning, the master workman pointed to the ash pile in the nearby stove. Unskinned potato – just baked.

Prison barack Dachau, image: Ministere des Anciens Combattants et Victimes de Guerre 45429

Prison barack Dachau, image: Ministere des Anciens Combattants et Victimes de Guerre 45429

This everyday routine from 4 in the morning till 6 in the afternoon brought about a total physical breakdown in a few months and I was taken out of the labor force. The return to „the disabled s’ barrack“ of the Dachau camp... Bare survival in the bunk, expectation of imminent liquidation, delayed only because the crematorium furnace was out of order. Preparations started for the dissolution of the camp and transportation of the inmates. Daily line-up at the „Appelplatz“, distribution of three-day dry food rations, air-raid alerts and return to the barracks. Explosions could be heard from afar, but soon gun shots from closer by as well. A group of American reconnaissance soldiers broke into the camp grounds. Exchange of shooting with the remaining SS guards, their surrender, and finally liberation of the camp in the afternoon of April 29, 1944.

Dachau...freedom...April 29, 1945

Dachau...freedom...April 29, 1945

Even in the „disabled s’ barrack“, some people were getting up, going out, there was a crowd of milling camp inmates, and between the barracks, on the way to the „Appelplatz“, there were the liberators – American soldiers. Thousands of inmates joined together, those who did not get to be transported. They were all embracing each other, kissing, shouting out, laughing, rejoicing in the freedom. I remember my slow wobbling steps, as I staggered along with that blazing crowd of people. I can still see the crowd progressing towards the kitchen quarters and storerooms, some people are finding empty dishes with meagre food remains. They are scraping the inside of dishes with their hands, removing the remnants of some soup that stuck onto the surface and putting them into their mouths. They are calling out: food, food. They are opening the nearby store-room, I can see some of them already opening cans with food and eating out of them. The next day we, the „wobblers“, stepped on the scales in front of an American physician - 44 kg, height 178 cm. We were taken to a temporary hospital. A month later, a truck ride to Ljubljana and from there, in an open freight carriage, all the way to Čortanovci, the torn-down tunnel, and then on foot to the other side and back to Petrovaradin and a ferry across the Danube to Novi Sad.

Pavle Katić

Pavle Katić 2017